Chapter Fourteen - Beneath the Passing Clouds

|

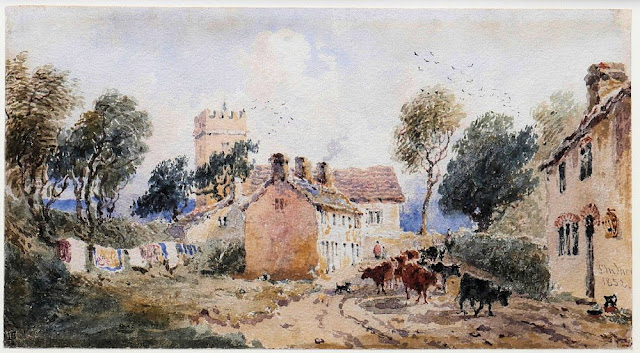

| Painting by Joseph Murray Ince, A View of Radnorshire, 1839 |

|

| Edward Joseph Ince's baptism entry, St Edward's Church, Knighton, 20 Jan 1829 |

|

| 1830 Presteigne Land Tax Assessment showing Henry Ince as occupant |

|

| Men Scything, sketch by Joseph Murray Ince, 1829 |

|

| Description of the house Henry and Charlotte leased from James Stephens from an 1821 advertisement in the Hereford Journal |

Some things never change – market days were still on Saturday, and the June Fair at the Warden was the festival of the year, never to be missed. The church day bell still rang so early at five on summer mornings and sounded curfew at eight o'clock every evening all year round. The Meyricks were the butchers, James Beebee was the rector of Presteigne, John Davies was the miller, and Charlotte still eyed every hat in the dress shop on Broad Street since the time she was a little girl. Henry's cousin Susannah still doted on his every move, and always news would spread through the parish like spilt molasses, taking its time, gathering more tarted-up gossip. Still, there was an unexplainable comfort in being back, found in each step Charlotte took. To her, it was the place where familiar footpaths carried her to wherever she wished, where each bend in the road, no matter how mundane, revealed how close she was to where she was going. If there were any ill feelings remaining towards her by Henry's family and associates, surely the subject was becoming dull by now.

|

| View of St Andrew's Church, Presteigne by Joseph Murray Ince, 1852 |

The seating of Radnorshire's Great Sessions was held in Presteigne's new Shire Hall for the first time that August. Only three prisoners were brought before the court. James Roberts received a death sentence for stealing a horse, but in benevolence, the verdict was changed to transportation for life. Still, a hefty sentence. The other two prisoners had been accused of stealing wearing apparel; William Pope, otherwise known as Protheroe, was sentenced to fourteen years transportation, and Mark Jones received one year of hard labour. Even though the gaol at Presteigne was relatively new, frequent breakouts continued, as they had in earlier years. Security upgrades were lacking, possibly due to poor wall construction, jailers' oversights, or simply good fortune on the prisoner's part. Either way, many of the townspeople just chose to look the other way. Less than three months earlier, John Pugh, under a sentence of transportation for stealing a goose, made his way out with his dirty smock-frock, grey smock coat, an old light-coloured waistcoat, kerseymere breeches, strong nailed shoes and a very old hat. It is said that Radnorshire jurors tended to sway slightly in favour of the accused, to the extent that it was once reported that a judge, being driven to Knighton, saw a hare running across the road chased by two greyhounds. "Nothing but a Radnorshire jury could save that hare", he said. Charlotte would likely smile at such a statement.

|

| John Pugh's Escape, Police Gazette, 6 June 1829 |

It is likely that Charlotte's unmarried brother, Samuel Vaughn, now in his early twenties and listed as a farm labourer in later years, was working on the farm with Henry. An acre of fruit trees could be a hundred or more trees, and Henry was planning on a good supply of pears and apples. The potato plants were already beginning to wilt, signalling they would soon be ready to dig up. Charlotte was pregnant with their third child and had no time to rest. Even on a small scale, her responsibilities would include milking cows, feeding pigs and chickens, baking bread, churning butter, preparing meals, laundering and mending clothing, while caring for both an infant and a toddler. They likely hired a young girl to help, and it would not be surprising if Charlotte's mother, Ann, lived with them for a time. The heavy downpours of August may not have troubled Henry and Charlotte's modest garden, but nearby, the River Lugg and its tributary streams had overflowed, playing havoc with the lowlands. Fields and pastureland throughout the area were damaged, causing a loss of wheat and clover for some of the neighbours. Henry hoped the hay they had would carry them through the fall.

|

| 1829 Radnorshire Game License List, 30 Sept 1829, Hereford Journal |

In September, Henry's name appeared for the second consecutive year in the Hereford Journal's list of those who obtained game licenses in Radnorshire. Family friend Dr. Edward Jenkins was also on the list, as was John James. A typical hunter was no longer one who headed out into the wilds of the forest; those days were long gone. To hunt, Henry had to purchase a license, which, at £3 13s 6d, was quite costly. Hunters were required to own land valued at £100 or more per year or lease land worth £150 annually. If you were the eldest son of a high-status gentry, a person of high degree, or fortunate enough to be invited by a landowner, you could be an exception. Those who did not qualify could not own a hunting dog, and individuals with smaller plots of land could not shoot any game that entered their property, even if it destroyed their crops, unless it was a rabbit, but not a hare. Game was defined as pheasants, hares, moorfowl, and partridges and did not apply to all animals. Although no one truly owns a wild animal that roams about, with ongoing enclosures of fences and hedgerows in favour of those that owned the land, deer, ducks, and rabbits were now regarded as semi-wild and considered the property of the landowner.

|

| The 16th-century Flemish tapestry depicting Christ entering Jerusalem was presented to St Andrew's Church in 1737. Now hanging on the wall, it was initially used as an altar cloth. |

As September readied to slip into October, when the sky against the colours of the trees was so blue, Henry and Charlotte brought their two children to the parish church to be christened. It was Wednesday, September 30, the day following Michaelmas, signalling the return of autumn and one of the traditional quarter days of the year when leases commenced, rents were due, servants were hired, and legal matters were settled. St Andrew's Church was where Charlotte stood several times before with her first three babies, but this walk up the gravel path marked an entirely new season for her.

At first, it seems like there may have been two baby Josephs born. However, based on the baptism of Henry and Charlotte's third child, who is now due to be born in the spring, and counting backwards to the baptism of the last baby she had with Henry P. Pyefinch, there appears to be not enough calendar months for a fourth child to have been born. Church doctrine states that a baptism can only be performed once. Still, the thought crosses my mind that as a newborn, Joseph may have been sickly and, therefore, quickly baptised at home. Yet in that case, unless it was believed that the ritual was performed incorrectly, which is doubtful since it was officially recorded in the Knighton register as performed by the Reverend Robert Morris, baby Edward Joseph would have only been introduced into the congregation and not rechristened. It is likely that Henry and Charlotte simply wanted their children baptised in their home parish so that family members could attend. Another thought is that Charlotte was a nonconformist, as was much of Henry's family, and so in no rush to have the children christened. Or, when looking ahead to Charlotte's future years, perhaps she was considering converting to Catholicism and waiting to come to an agreement with Henry over the children. Whatever the reason, in coming to know Charlotte, I see her, out of fear for her children's souls, going ahead with any holy baptism, even twice or forbidden, just to be sure.

|

| Parish baptism entries for Henry Robert and Edward Joseph, 30 Sept 1829, St Andrew's Church, Presteigne |

Traditionally, there were to be three godparents. Two men and one woman for a male child, and two women and one man for a female child. Joseph may have travelled in from London to take part, or perhaps Edward Jenkins stood as godfather. Charlotte's siblings may have been chosen. Curate Meyrick Beebee, who often filled in for his father, the Reverend James Beebee, officiated. Charlotte and Henry, with their young sons, stood ready by the ancient stone font filled with the purest water, accompanied by the godparents. Curate Beebee began the ceremony, echoing the words that had been spoken in those walls for hundreds of years, with the opening statement as it appears in the Book of Common Prayer: "Hath this child been already baptised, or no?" Surely, they would answer no. Soon, infant Edward Joseph was back in his mother's arms, with Charlotte and Henry keeping the mystery to themselves.

|

| Rural scene by Joseph Murray Ince |

Autumn's mild weather was put on hold when suddenly, in the first week of October, the Radnorshire hills were draped with snow. The weather soon changed to heavy rain and sleet, glazing the fields and harvest wagons with ice. So sharp and piercing was the cold that some say it was the coldest day of the year. Yet, as quickly as it appeared, the seasonal days returned. Henry and Samuel hurried to collect the remaining harvest, half expecting another display of winter's whimsy to catch them off guard again. Henry turned thirty-two that month. Generally, birthdays were not celebrated with much fuss - that came later over the years. Although Henry's mother likely invited them for a goose dinner or perhaps sweets with tea. The backgammon set would come out. Henry's father's namesake would be pulling on his leg to see, while Edward Joseph finally napped on Charlotte's lap in the far corner of the drawing room.

There,

the secretaire was filled with books, its glass doors barely able to close. It

was a place where Charlotte welcomed losing herself in the moment. Trying to

catch each title out of the corner of her eye, she could hear their quiet

conversation brush from one topic to the next - Henry's cousin George and

family were travelling to America. Were they planning to see his father in West

Virginia? Uncle Thomas Willson's pyramid cemetery plans continue to entertain

the London papers, and Joseph has not stopped painting since the last time they

saw him. Mr Ince was eagerly awaiting the outcome of an upcoming meeting of

county magistrates and freeholders in the hope of keeping the Assizes in

Radnorshire. Relocating them to Hereford in England would only injure the

welfare of the county, he said. With each tick of the clock, Charlotte's

thoughts were still upon the bookshelf. She eyed several worn volumes of

medical journals she remembered seeing on Henry P. Pyefinch's busy desk. And

just like that, a simple book carried her further back than she dared to

remember. She knew that any day now a note would come, stamped in black

sealing wax, to her door.

All Hallows' Eve approached. It was a Saturday, a night with no moon, only stories of hellhounds and spirits passing like the wind in the sounds of wild birds. It was when people walked faster to hurry to their hearths, and tradition predicted abundance, death, and marriage - and the day Henry Pateshall Pyefinch died at his home on Broad Street.

The bell tolled nine times on the morning of his funeral. While a fancy horse-drawn hearse decorated with plumes and velvets might have been an option, Henry P. Pyefinch's coffin was likely carried to the parish church, as it was located just down the street from his home. A procession of family members, colleagues, associates, and townsfolk who had come to rely on his doctoring over the years gathered behind, the men wearing black armbands and gloves, the women in sombre colours and black ribbons on their hats and bonnets. They would pause at the lynch gate, awaiting the Reverend James Beebee. Then, close friends and family would follow. Henry P's niece, Mary Stephens, would be there with her brother, his nephew, John Taylor Stephens, as well as his cousin, John Bird, and close friend and sole executor of his estate, John James.

Charlotte was not his widow, but she would wear black. Now, at age twenty-one, she felt as if she had spent a lifetime with him. He had taken her from servitude to mistress to motherhood. He understood when she wanted more from life, when his love was not enough, when their social differences still held the reins on what he could not shake. He had been her security, even with no strings attached; he watched over her, cared for their children, and gave her a life. In his will, Henry P. Pyefinch acknowledged his natural children and secured their future apprenticeships, as well as their inheritance. And now there she stood in the churchyard, where they once stood, filled with the loss of their youngest child, this time trading white spring blossoms for the muted gold of sycamore trees that lined the walkway. Even now, Charlotte found herself comforted by his words when, in fact, she knew she should have been the one comforting him.

|

| Henry P Pyefinch's death notice, 18 Nov 1829, Hereford Journal |

|

| Henry Pateshall Pyefinch's grave inscription. He died close to the time of his 60th birthday. |

Henry P. Pyefinch's grave is marked by an altar tomb that was later shared with his nephew, John Taylor Stephens. It rests near Broad Street, alongside what was later known as the Old Bridge Inn. Charlotte would pray for his soul, and when she had a moment free, such as on market days or during last-minute errands to town, she would take a longer route to pass by his grave, to finish the words she couldn't find and watch the last of autumn's leaves swiftly swirl away.

And so now, it was suddenly December, with the days closing in so early across the hills. Charlotte's sister, Ann, and John Abel recently had a baby boy named George Abel Vaughn, baptised on the twenty-first of the month at the parish church. The family gathered together, and Charlotte had plenty of apples to make a proper tart. Ann and John lived on Scotland Street with John's mother, Hannah. They had posted marriage banns two years prior, but whether they decided to postpone the ceremony or were wed outside the Church of England remains unknown. Until 1836, marriages conducted within another denomination were not considered legally binding, and the children typically carried their mother's surname. The twenty-first was also St Thomas's Day. Like the women of the neighbouring farms, Charlotte set a sack of wheat outside her door for "thomasing" - when the women would go farm to farm, collecting a quarter measure of flour to add to their supplies, which they often saved for Christmas baking. It was also a day welcomed by the poor cottagers, who were permitted to ask for their share as well. To refuse them, they say, was very unlucky.

The solstice brought the promise of light, and the year prepared to end the way it began, with sudden, subtle snowflakes wandering the heathland. Frost gathered in the dingles and valleys, and peat smoke leaned from their cottage chimney. Charlotte's life was always a journey of change, but this time she was happy for the warmth of winter dreams. While Henry made a final check on the livestock and the last rush candle of the night burned low, Charlotte glanced at Henry and Edward nearby in their cradles, hoping they were sleeping peacefully, smiling, seeing angels.