Chapter Ten - Beguile the Time of the Curious

|

| The Thames at Twickenham by Joseph Murray Ince |

Unanswered muses were peeking out from under the carpet, leaving Charlotte's imagination to twist and turn. She knew Joseph would be doing the same. While Henry sat focused, listening to Uncle Thomas Willson describe his plans and visions on paper, conversations lingered to places and points of history further than Charlotte's thoughts had ever travelled. She found her eyes widening, looking straight into their faces with an unabated look that gave her thoughts away.

There was a thread of passion woven throughout Henry's family, ranging from artistic to intriguing and even seemingly outrageous. To Henry and Joseph, it was customary, but to Charlotte, it was spectacular. How clear it was that this was not the life she had tucked away in Presteigne. Here, she was greeted by an array of daring visions- dreams that were actually sought. Creating a new chapter with each turn of a page, thus, this one begins.

|

| Mary Ann Ince and Thomas Willson's parish marriage entry, 13 August 1808, St Botolph Aldgate, London |

Uncle Thomas Willson, an architect, was married to Henry's father's youngest sister, Mary Ann Ince. She and Thomas were now in their middle forties with four children: Percy Cowell, age sixteen; Mary, age fifteen; Douglas, age thirteen; and Thomas Jr, age eleven. In 1800, at twenty years old, Thomas had been received into London's Royal Academy. His plans for a national monument won a gold medal there the following year, an accomplishment for his youthful age. He worked as a surveyor at Horse Guards, the British Army headquarters in Westminster, where he illustrated the campaigns of the Duke of Wellington and later surveyed for the Chelsea Waterworks, a company that supplied water to much of central London. They resided in rural Stockwell, Surrey, approximately three and a half miles south of London, at Belmont Cottage on Love Lane (renamed Stockwell Lane in 1937), an area where Thomas' father, Archer Willson, lived and worked as a builder and bricklayer. Archer Willson had an agreement with the Duke of Bedford to construct houses on part of the old Stockwell Manor estate, and the Duke of Bedford would lease them. The cottage Thomas and Mary Ann were in could very well have been built by his father.

Thomas Willson was described as a “great mind,’ “a considerable talent, capable of gigantic achievements.” He seemed to make a good impression, but when it came to money, it did not come easy for Thomas. The household was lacking, but not from lack of imagination.

Their home was a wealth of knowledge and with more books and sketches than Charlotte could catch sight of. Although easily accommodating for a family of six and two servants, I am sure it looked lived-in and a bit more modest than expected. Charlotte would find that refreshing. Across the room, alongside a mahogany desk with a tilted top, one could picture architectural models set on wooden crates - all Thomas' creations and from where Charlotte was sitting, she would try and explore each one. Conversations would saunter from the news of the day to the latest family meanderings. Thomas talked of a new mode of transportation he recently read about in the Morning Post - a carriage to be propelled through a tunnel by the atmosphere. They joked how they needed it this morning when crossing the busy Westminster Bridge. Aunt Mary Ann joined in, praising the weather, commenting on the branches filling with berries and how soon the season would change. She talked about their trip to France last summer where Thomas continued research on his latest project. Henry’s aunt was undoubtedly devoted to her husband, and just from the little time Charlotte spent with her, it was obvious she was willing to go to great lengths to support him.

Six years earlier, Mary Ann, with their three young sons, ages nine, seven and six, accompanied Thomas in leading a party of settlers, a group of over three hundred individuals, to the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa. The undertaking was a disappointment to Thomas. Thomas felt that with the time he put into recruiting the families and organising their means of survival, he earned the title of Lord of the Manor, a proposal he presented prior to leaving London to Lord Bathurst, the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies. Such entitlement did not go over well with a group of tired settlers far from any comfort of home who had been trapped in the ice-bound waters of the Thames for more than a month before setting sail on a three-month-long journey with strict rations, finally arriving in Algoa Bay where they lived in tents before taking part in a caravan of over sixty wagons heading into the wildest land they had ever seen to build homesteads with every remaining ounce of stamina they could muster - no it would not end well.

Thomas was required to collect a deposit of ten pounds from each settler. He collected an additional five pounds, claiming it would secure further needs and that it would be returned to them in time. However, the Colonial Government did not agree to return the money. The settlers were turbulent, surely already bitter over his toplofty "Lord of the Manor" tendencies and accused Thomas of keeping the money. It appears he may have been set up for he was not a thief, and is worth noting that he refunded the deposit money out of his own pocket. Before leaving London, whether out of kindness or obligation, Thomas paid deposits for several settlers, as well as that of a clergyman and family. It soon became clear that Thomas never had enough funds to cover such an endeavour.

|

| The red marker shows Port Elizabeth in reference to its location in South Africa. |

|

| Thomas Willson's 1819 circular outlining his plans for the settler party British South Africa, by Colin Turing Campbell, London, 1897. |

When they reached their destination in the Albany District, Thomas abandoned the settler party. Thomas was not one with a lack of words, and so I have read dozens of his letters to the government yet still cannot conclude the exact reason they left. Perhaps he was disenchanted after his expectations of creating a settlement the way he pictured it in his architectural scheme named Angloville, believing himself to be the proper custodian. Or maybe the unfortunate events, confrontations and threats, as stated in his letters, caused him to fear for his life and that of his family. Looking into Thomas' future years, it was not in his nature to give up. Could it be that Mary Ann's happiness outweighed his own? He mentions her fondly throughout his life and holds her in high esteem. He was tenacious. Yet, her health was not good. Could it be it was just too much for her and their three little boys?

|

| Letter written by Mary Ann Willson nee Ince (my 5th great aunt) to Acting Governor, Rufane Shaw Donkin, Port Elizabeth, South Africa, 20 August 1820. |

What is known is that Thomas was now destitute, having to depend upon the government for help. For a while, he farmed and appears to have settled on land. In Port Elizabeth, Thomas designed and helped to erect several timbered buildings. He mentions money stolen that he had set aside to build his mill and later having to forfeit a winnowing machine that was left unreturned to him. He sent out letters applying for government jobs in Cape Town to no avail and later remarked having sold off their possessions and left with very little. He mentions the death of his father. He continuously met misfortune with a noted Captain, who appeared to put a heavy foot in every direction he turned. There were prejudices of social standing, religion and the country you hailed from and little time or tolerance for those who complained.

|

| Algoa Bay, 1820 |

|

| Thomas Willson's letter to Lord Charles Somerset, Governor of the Cape Colony. Written in Simons Town, Cape Town, on 29 August 1822, two months before their return to England. |

Thomas, Mary Ann, and the boys remained in Cape Town awaiting passage. Overcrowded vessels and heavy storms delayed their travels. Finally, on the twentieth of October 1822, they departed Simon’s Bay, Cape Town, on board His Majesty’s ship Leander, sailing into Portsmouth on December 10th, 1822, disembarking the following day due to a quarantine. It was just a month short of three years since they set off on their settler dream. There was humiliation in all of this, but with a lack of money in his purse and highhanded expectations, I wonder if Thomas ever understood how much of it could well have been his own doing.

_-_HMS_'Leander'_at_Sea_-_BHC3442_-_Royal_Museums_Greenwich%20edit.jpg) | ||

HRM Leander, painted by Thomas Buttersworth, 1813.

|

Upon their return, with little funds, Thomas Willson continued to look to the government for reimbursement of his deposit money, claiming he successfully delivered the settlers and was deserving of a grant of land. The government reminded him that he did not stay the required three years to receive acreage and that much of the deposit money was not his own. It drained Thomas. He never got over it, and with each letter he wrote, he got the same reply – no. Even now, as Thomas struggled to gather just the right words, his financial situation pressing the matter, half-penned letters lay forthcoming on his desk. "To the King's most excellent Majesty, the humble Petition of Thomas Willson, of Stockwell, Gentlemen, Head of a party of Settlers of one hundred families consisting of upwards of Three hundred Individuals whom he located in the District of Albany, Cape of Good Hope, in the Year 1820; under a pledge previously obtained from Your Majesty's Government that he should be reimbursed in his Deposit Money…."

|

| Thomas Willson's letter addressed to the King, October 13th, 1826, Stockwell, Surrey |

The temporary governor of the Cape of Good Hope, Sir Rufane Shaw Donkin, arrived in Algoa Bay around the same time as the Willson party. He soon renamed the town Port Elizabeth (today called Gqeberha), in memory of his wife, Elizabeth Frances Markham, who died in India two years earlier after childbirth. Sir Donkin was so deeply affected by his loss that he commissioned a pyramid to be built in her honour. Thomas Willson designed the pyramid. It was constructed by soldiers in August 1820 using local stones – all within the span of a month. It still stands today.

Henry and Joseph knew it was best not to broach the subject of Cape Town. They heard the family say many times that Thomas was an artist, but a leader he was not. They would let it rest. Still, the vastness of their uncle’s dreams seemed to push theirs along. They looked up to him. It was in unspoken thoughts of this that the subject of pyramids came up.

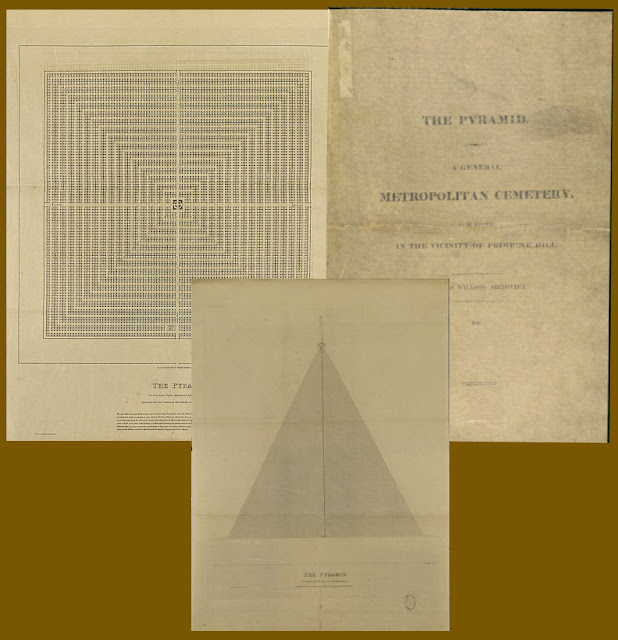

Thomas had a new plan. One that beamed beyond description and appeared almost as a madness. Whatever the passion was that Charlotte caught in his eyes, it exceeded the scope of a few workmen and bricks. It was a project bigger than anything he attempted before. Within a spell of words, without hesitation or any fear of dismay, Thomas introduced his latest project. He called it The Pyramid, a Metropolitan sepulchre, an enormous pyramidal cemetery.

|

| Thomas Willson's pyramidal sepulchre plans for what became his lifelong project |

He described it in complete detail. Made of brick with granite facing, it would sit upon London's highest point, Primrose Hill. At a majestic ninety-four stories high and approximately fifteen hundred feet tall, The Pyramid would be over four times the height of St Paul's Cathedral, which, at three hundred and sixty-five feet, was London's tallest building until the 1960s. Such a concept is almost impossible to grasp.

|

| Primrose Hill, London, 1780, painting by William Henry Prior |

Inside the pyramid, there would be a honeycomb of vaults, evenly divided and accessible with corridors. The vaults, "secure from the ravages of time", would hold up to five million bodies arranged in numerical order. There would be ramps, a hydraulically powdered lift, a chapel, as well as living quarters for the sector, groundskeeper, and registrar. Outside, in a park-like setting, there would be walkways and undisturbed places for loved ones to gather. Thomas described it as "simplicity with grandeur, a "Wonder of Britain” and a "pious veneration to posterity."

|

| Thomas Willson's Plan for a Metropolitan Pyramidal Cemetery |

Perhaps there is an explanation for all this puzzling ostentatiousness. Thomas, without doubt, believed this was the answer to London’s looming burial problem. Churchyards were filling up faster than ever. Decayed bodies were being removed from old coffins to make room for the new dead, many clustered so closely together they lifted from the ground. Deeper graves were dug, people buried one on top of another, and to allow even more space, sometimes interred without coffins at all. Cremation was still not widely acceptable, and while coaches carried the deceased further and further into the outskirts, the fear of “noxious vapours “and mounting unsanitary conditions in graveyards delivered more health concerns to a city already teeming with diseases.

Yet to Thomas, it was more than just a tomb. It was a myriad of wonder. A symbol of mystery rising above the skyline in celebration of life, death, and eternity, evoking a sense of reverence. It would remain his lifelong mission. Despite the strangeness of Uncle Thomas' mind-boggling plan, his words speak to me: “....to trace the length of its shadow at sun-rise and at eve, and to toll through its chilling width will beguile the time of the curious, and impress feelings of solemnity and wonder upon the astonished traveller.” Thomas dreamed as both a poet and artist.

Charlotte would not question a dream, but she would be dumbfounded. I wonder what would catch her off guard the most, picturing a cemetery reaching up to the sky or how Henry’s uncle seemed so untouched by ridicule or public displeasure. Maybe she wondered if it was just London that made one's imagination so huge.

|

| Richard Pococke, 1743, taken from the frontispiece of his book on his early travels in Egypt |

Percy, the oldest, clearly shared his father's enthusiasm, as did his sister Mary Ann. They had learned so much from watching him. It did not surprise Charlotte that Mary Ann, a young woman, understood the basics of drafting, but she knew others would be surprised by such a thing. It was a step forward in their rigid world, and Charlotte began to envy her for that. Aunt Mary Ann invited them for St Michaelmas day, for she would be cooking a goose. Uncle Thomas suggested they visit the Galleries of Antiquities at the Royal Museum before they return to Hertfordshire, saying the eighth room has the mummies and the ninth room, with the tomb of Alexander the Great and the Rosetta Stone, is the gem of all. Douglas and young Thomas joined in with playful comments on mummies and sphinxes. Charlotte could not help but laugh and wondered if they grew up dreaming in hieroglyphics. In a moment's thought, she was confident that they all still do.

Charlotte had seen so many things these days - Hyde Park with its Serpentine River; Hackney coaches available at the wave of a hand, if you have a shilling a mile, that is. She met the Willsons and saw the places Henry knew as a child. She walked across the Westminster Bridge, ate in a chophouse, caught a glimpse of Vauxhall Gardens, and saw herself in a tall, gilded mirror with a new winter hat upon her head. Yet what stood out the most was that just like Thomas Willson was willing to risk so much in pursuing his dreams, silent Henry, the one in the uniform standing straight and proper, was willing to put everything on the line for her.

<><><><><><><><><><><><><>