Chapter Twelve - Before the Month Was Out

The new

year arrived in mild weather, with the weeks slipping suddenly into snowy

walkways and shivers of freezing temperatures. Pots of ox head soup simmered on

hearths filled with leeks and turnips, thickened with oats or barley and

perhaps an extra dose of black pepper to warm the spirits. Ponds came to life

with skaters, and forgotten stashes of snowballs sat frozen like miniature

monuments. Visits in winter were less and less but all the more welcomed, and

while evening candles in the windows charmed through the frostwork like a

mosaic, wagons and peddlers trod on, anxious to reach their day's end

destination.

In

February, more than three hundred townspeople suffered from ague in Tring, the

small Hertfordshire market town where Charlotte and Henry appear to be living.

Ague, sometimes called Marsh Fever, was later known as malaria. For those

unable to obtain quinine, an assortment of home remedies was sought, including

Epson salts, ginger, as well as hartshorn mixed with brandy and vinegar to help

ease the severe chills and fever. Days remained dismal until sometime in April

when the hawthorn and silver birch began to awaken, and a cuckoo signalled its

brief return. Still, the cold held on mightily until nearly June when sprays of

Queen Anne's lace and lilac-coloured vetch finally charmed the roadsides.

Charlotte could not help but notice that as long and hot as the last summer

season was, this winter's hold, as if in complete opposite, was just as

tenacious and intense.

|

| Ague in Tring outbreak, 11 March 1827, Sunday Dispatch, London |

With

each family letter Charlotte posted, it felt like a lifetime awaiting a reply –

if she received one at all, for it seems only Charlotte among her siblings

could read and write. She would rely on Henry or Joseph's letters from home to

keep her in touch with goings-on. Charlotte's oldest sister, Ann, was due to

give birth to her fourth child in May. Charlotte would be waiting anxiously to

hear how mother and baby were doing. Surely, Ann must be living with John Abel

and his widowed mother on Scotland Street by now. She heard they had posted

banns intending to marry at the chapel in Discoed before summer. Here,

Charlotte had the freedom of being far from the life she feared would lock her

in place, yet she was left with a longing that sometimes cut through her so

painfully. Without a doubt, her nieces and nephews would be climbing the path

up to the Midsummer Fair, among the familiar chestnuts and broad oaks, glancing

across the hills – their ribbons entwined like those with her siblings not all

that many summers ago. She found herself a bit more emotional than she dared to

reason with.

|

| Charlette's sister, Ann Vaughn and John Abel Banns of Marriage, Feb, Mar, Apr 1827, Discoed, Radnorshire, |

Still, time passed, measured by the events of Henry's family. Henry's mother was sick. She had been unwell with dropsy for years, and her condition was getting no better. Little was known of the cause, and Henry's father would do what he could to ease the pain and swelling. Newspapers were always advertising cures, and Henry's father would follow medical updates closely. At the time, it was unknown that dropsy was not a disease but a symptom of an underlying matter, such as diabetes, heart failure or a kidney disorder. Later in the year, in London, Dr. Richard Bright, who came to be respected as the "father of nephrology" and after whom Bright's Disease was named, would publish his first medical report on dropsy.

|

| Dr Richard Bright's upcoming report on dropsy, 21 September 1827. Morning Chronicle, London. |

Joseph

was planning to go to Stockholm the following year. This would be his first

trip abroad, and he was anxious to move forward. He had spent summers painting

seascapes on the Sussex coast and, on several occasions, accompanied his former

teacher, David Cox, to North Wales, his teacher's painting style so evident in

the movement of Joseph's trees and shadows. Last year, David Cox left Hereford,

where Joseph had boarded with him for three years as his apprentice, and

relocated to London, to continue his work as a painting master. His

talent was no less than his noted contemporaries and friends, including JMW

Turner, but he was from humble means and with a wife and son to support. His

teaching would carry him through while awaiting the sale of paintings. Cox had

written 'Treatise on Landscape Painting and Effects in Watercolours', a booklet

filled with examples and studies. I would be surprised if Joseph did not memorise it in its entirety.

|

| Joseph's mentor and friend, David Cox, painted by William Radclyffe, 1830 |

| |

Treatise on landscape painting by David Cox, 1814

|

In London, Joseph had moved further down Oxford Street, closer to where his Ince grandparents had lived. He rented a room at 55 Newman Street in an area lively with art supply shops and working artists seeking short-term housing. At 34 Rathbone Place, one street over, stood the delightfully whimsical Temple of Fancy. They were publishers and print-sellers who specialised in everything to "shew and use". Through the entranceway, an island of glass cabinets caught one's eye, filled with tints, inks, brushes, figurines, and trendy sketches of Paris fashion. Shelves lined the walls with an endless variety of novelties. There were games, working tables, colour boxes, Bristol board, wallpaper, tea caddies, lithographs, and more. Their street address was also the address listed for Joseph that year in the British Institution for Promoting the Fine Arts' exhibitor catalogue. His landscape, 'Village of Eardisland, Herefordshire,' was displayed there recently, and two other paintings, "The Banks of the Lugg" and "Near Dolgelly" in Wales, were currently on exhibit at the Royal Academy, which opened in mid-May. His hope of acknowledgement as an artist was coming into play.

|

| Opening of the Royal Academy Exhibition, 14 May 1827, Morning Herald, London |

|

| Temple of Fancy, Art Supplies & Fancy Goods, 34 Rathbone Place, London, 1823 |

|

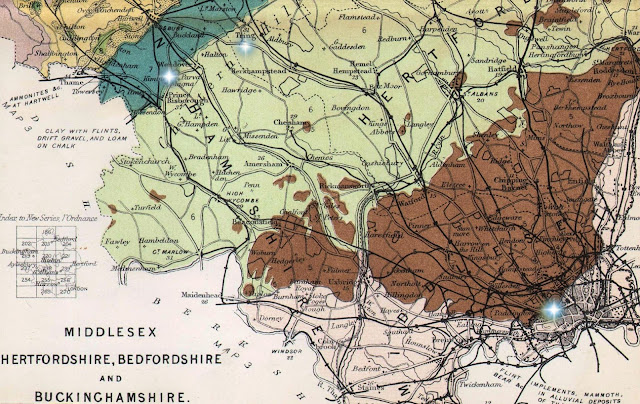

| Map showing (left to right) Wendover (Henry's birthplace), Tring (his son Henry Robert's birthplace) and London (where Joseph and much of Henry's aunts, uncles and cousins lived). |

|

| Cottage in Wendover with the church in the background as described above, Joseph Murray Ince, 1827 Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, South Hadley, MA |

Late

August brought rosehips and blackberries. The fields were full of grain now.

Fairytale toadstools sat under the brush, and heavy clouds and shifting sun

tinted the sky a bit earlier each day. Children were sent out a-nutting in the

hazel woods, racing the squirrels and dormice to the bounty. Charlotte found

herself altering her favourite dress for a bit more comfort, all the while

waiting to confirm what she already knew. She was tiring easily, and Friday's

market days left her anxious to return home to sit awhile. The baby's

quickening would come soon enough, and with the first flutters of motion, she

would write a note to her mother and sisters, imagining somehow that they might

join her. This would be Charlotte's fourth child in a little over four years.

She was very familiar with the routine and what could be expected but had never

gone through her "time of trial" without her mother and sisters. Nor

did she have Henry Pyefinch, who, as a physician, obviously took an active part

in the previous births. First times always come with a dose of apprehension.

This pregnancy would be different, though – she was married now. And she certainly

knew what it was like to fall short of that in the eyes of tainted society.

Henry

was ecstatic, and anticipating his first child. He had little idea how he would handle additional financial

hardship, but he would always be there for the children, whatever the

circumstances. He proved this in years to come. Yet a mystery piques my

curiosity - what brought Henry and Charlotte to the Tring area? Could it be

what also brought his parents to nearby Wendover at the time of his birth?

Henry was still an officer in the Royal Berkshire militia, yet his pay as a

lieutenant would be nominal considering the militia's inactivity. He would need

to supplement his income. Soldiering and an interest in farming are the only

two pursuits found for him in the way of employment. Perhaps the opportunity

came to give farming a try.

There would be scarcely any talk publicly about Charlotte being in the family way. Pregnancy was a private matter, shared only with the closest family members, dear friends and possibly a neighbour who could be called upon in a time of need. Henry would remain quiet; men just didn't talk about those things, knowing all the while it would be hard to prevent his aunts and female cousins from not guessing what was keeping them from family visits.

September brought a brilliant display of Northern Lights, just a few days before St Michaelmas Day, with the sky appearing to be on fire and waves of light rolling past midnight. It was the first time seen in southern England since the autumn of 1804. October brought Henry's birthday on the third of the month. He turned thirty years old. The day would probably pass by without much thought. Birthday celebrations were saved for the upper middle class and beyond. Most people did not even know the date of their birth. This would gradually change when civil registration came about in 1837, and birthdates would be required. In November, Uncle Thomas Willson's pyramid cemetery proposal flooded the London papers, placing his scheme somewhere between genius and madness. December brought the start of winter, complete with mummers, Christmas roast beef, benevolent donations and London's return of nobility and gentry to ready the opening of Parliament. Near where Joseph was living was where cousin Caroline Ince, the daughter of Uncle Frederick and Aunt Martha, had lived with her husband, Benjamin West, at the home of her father-in-law, Charles West, on Great Portland Street. Although the family knew she was disheartened in her marriage, to the point where she did leave her husband for a while, very little was known about her sudden death. How they wished she had not returned to him. The loss of Caroline at the age of twenty left her family broken. Her funeral last New Year's Eve closed out the year beneath a heavy shroud. But now Henry dared to believe this year would bring much brighter things to come.

|

| Northern Lights, 26 September 1827, The Standard, London |

It was

customary for a woman to spend much of her time in bed for at least several

weeks before giving birth and after, but who would be there to help Charlotte

prepare meals, wash clothes and linens, sweep and make sure that she had

whatever was needed during her lying-in? Who would bring the spiced ale or

bread and barley water during labour? I can take the liberty of imagining who,

but only with the reminder of how little we truly know about the lives of our

ancestors. Was it her mother, Ann? Would she travel that far, leaving her job

as a servant? How could she afford to? It would not be her sister Sarah, who

was due to give birth about the same time as Charlotte, as was her

sister-in-law, Margaret. Nor would it be Charlotte's oldest sister, Ann, whose

youngest child, Susan, was but six months old. A possibility could be her

sister Elizabeth, but only if she were to leave her four young children in

someone else's care. None of it seems probable. Possibly, Henry's Aunt Isabella

Cowell helped in some way. Or Aunt Mary Ann Willson, but her health was not

good. Did Uncle George Saunders offer Mrs Stedman's kind service? Or where was

Charlotte's Aunt Elizabeth Roe? More than likely, they hired a young girl to

come in for a few hours a day. Much of what help would be needed would depend

on whether they were lodging with a family, renting the floor of a house with

or without a kitchen, living in town or further out in a humble country

cottage. This is unknown, but certainly, they could not afford to be excessive

without help from Henry's family.

|

| Evening by Joseph Murray Ince |

Winter was more like spring in January, with the grass so green from continual heavy rain. Even the birds were fooled by the lull in the season, singing louder than usual. Charlotte was not sure it was a good thing, for it was said that if birds sang before Candlemas, they would cry before May. Childbirth was a time of omens when everything carried meaning. Such stories covered the countryside of Radnorshire and moved like a mist beneath her door in Presteigne. She might shudder at the thought but would only consider it briefly, perhaps saying an extra prayer while crossing her fingers, just to be sure, of course. It was not in Charlotte's nature to fear the intangible. Her future was at hand, and she was anxiously optimistic.

Charlotte would have soft flannel ready to wrap the baby in, most likely from one of her old petticoats. The used cloth would be not just out of necessity but tradition. Henry would keep the fire going, ensuring the windows were shut tight. He would not want to take a chance of a draft getting in on mother and babe. Years before, they would even block the keyholes, and the curtains might be drawn for days, but now, many old practices were beginning to weaken. To help pass the time of confinement, Henry may read to her or relay news of the day, possibly stopping on his way home to buy one of her favourite sweets. Joseph would visit - the three of them chatting about opportunities, travel, and any news he may have on the family. This would be one of the last times in many years they sat together, unencumbered. Soon, there would be a baby to attend to, letters to write, and plans to make, but for now, it was time for rest.

Before the month was out, my link to Henry and Charlotte, Henry Robert Ince, my second great-grandfather, was born. Thank you Charlotte ;-)

|

| Fondly Gazing by George Smith, London |