Chapter Thirteen - The Ever-Changing Shadows

|

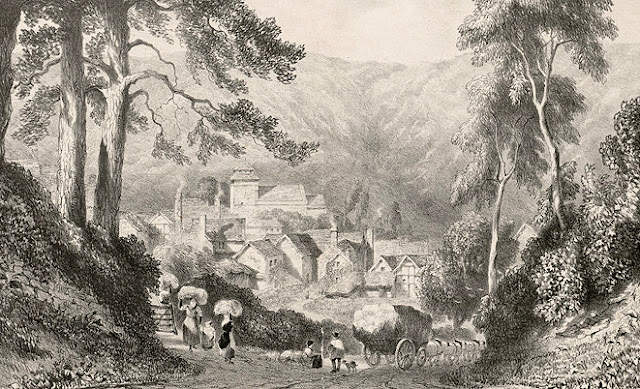

| Knighton, Radnorshire, lithograph by Joseph Murray Ince, 1831 |

Within the hills of the Welsh and English borderland, Charlotte and Henry had returned to Radnorshire. They set up house at Garth Cottage, about seven miles north of Presteigne, in the small town of Knighton. From their doorway, Offa's Dyke lingered nearby amongst the yews and holly trees, and the ever-changing shadows of green and grey shifted across the moorland. It was summer, and hedgerows filled with woodlarks and wrens. Daisies edged the hayfields, and sprays of leaves weighed heavy upon the branches. Charlotte could see why Joseph painted like he did, for with each subtle movement, the clouds caught her glance, carrying her thoughts somewhere over the next valley.

|

| A basic map of Radnorshire - Red dots showing Knighton and Presteigne |

Knighton, known in Welsh as Tref y Clawdd, meaning town on the dyke, was the only town situated on Offa's Dyke. The exact reason behind the eighth-century boundary between Saxon Mercia and the Welsh Kingdoms remains unclear - whether it was built for defence, as a display of power, or as a barrier to prevent either side from crossing. Parts of the dyke even appear to have been built earlier than King Offa's time. There are the remains of two Norman castles in Knighton. One was seized in 1215 by the Welsh prince of Gwynedd, Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, while in conflict with King John. Fifty years later, it was overtaken again, this time by his grandson Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. In 1402, the second stronghold, and much of the town, was destroyed by Owain Glyndwr, the last native prince of Wales, during his campaign for Welsh independence.

This is the marchland that Charlotte knew - wild and forgotten, having echoed its share of turbulent history - a small place, gifted with the lull of rivers and songs of the drovers, where a hundred mountains stretch over fifteen hundred feet high and where a ring of churches dedicated to St Michael keep a sleeping dragon in check. Charlotte could not help but walk in the paths of heroes veiled in tradition, for her spirit knew this place. She felt a lightness in her chest; she was home.

|

| Drovers Herding by Joseph Murray Ince |

As a mother, Charlotte lived her life in contrast. Baby Henry Robert kept her busy, and she was now pregnant with their second child due at the turn of the year, yet her firstborn, Joseph Jessie and her little daughter Matilda would never slip from her mind. A mother always wonders. Charlotte sent their father, Henry Pyefinch, a note requesting permission to visit the children. As a woman, she had no legal right to them. Her fate was moulded in his hands.

The visit was definitely an awkward one; the two Henrys greeted each other as gentlemanly as could be expected. The children were standoffish, but with a sudden sigh of relief when reaching for little Joseph's hand, Charlotte could see in his eyes that her son remembered her. With her hand in his, he quickly began to carry on about the minnows he had tried to catch down on the River Lugg that morning. The house servant Mary Humphreys must have accompanied him. For a moment, Charlotte felt an enormous tangle of jealousy until catching sight of three-year-old Matilda standing behind him. Matilda looked lost, her small hand nervously reaching forward, just as Charlotte had been taught to do at such an early age and for a moment, Charlotte saw herself in her daughter's face. With an exchange of fragile smiles, Charlotte did not know whether to cry tears of joy or remorse. All was soon restored when Henry Pyefinch's kind words assured her to call again before too long. Charlotte had not seen Henry Pyefinch in a year, but she could see there were things he was not saying.

Most likely, Charlotte welcomed the bit of distance from Presteigne, relieved not to be underfoot of Henry's family, for although she was happy to be near and cherished the time with her mother and siblings, it was obvious that Henry's mother was still distressed over their marriage. She hoped the time away would have eased the upset, but the silence only fed her uneasiness. Charlotte knew how to act in the company of gentlemen, but gentlewomen, even those of middling class, was a territory she had not yet conquered. Her footage was always unlevel. Henry's mother would not assume he would marry above his class, but she would never consider him to marry below his standing and certainly not with an older man's mistress who had borne three children. She would not see it as prejudice. She would just see it as the way things are meant to be.

Henry kept his mind on farming like his uncle in America and was convinced his mother would come around eventually. It did not help that his parents celebrated a marriage in London recently, described as a perfect match, when his cousin Charles Vogel Ince, a merchant and son of Uncle Charles Ince and Anna Maria, returned from Jamaica to marry their cousin Isabella Cowell, daughter of George Cowell and Isabella Ince. And to add to the sensitive subject of successful family matrimonies, the Cowell's son George Cowell, who officiated the wedding, would soon be marrying Frances Dakins, the daughter of the Reverend William Whitfield Dakins, Precentor of the Collegiate Church of St Peter Westminster (otherwise known as Westminster Abbey), and a chaplain & librarian to the Duke of York. This union would certainly raise the younger George Cowell's status and undoubtedly keep Henry somewhere beneath his mother's good graces. But Henry remained kind to his mother - her health was poor, and the recent loss of her older sister, Susanna, had broken her heart. It was while attending Charles and Isabella's wedding that word came to the family of Aunt Susanna's death in Yorkshire.

|

| Henry's Aunt Susanna Gray Saunders, wife of Fletcher Rigge, death notice Newcastle Courant, 24 May 1828. |

|

| Royal Palace, Stockholm, Sweden by Joseph Murray Ince, 1829 |

Joseph was in Sweden preparing at least eight paintings, including those of the Royal Palace in Stockholm. It seems likely he travelled in part with his cousin, William George Meredith, a grandson of Henry and Joseph's mother's brother, Edward Gray Saunders. William, who was in Sweden doing research, attended Brasenose College in Oxford and was working on completing his Master of Arts degree. William was as passionate about history as Joseph was about painting. His book, The Memorials of Charles John, King of Sweden and Norway: with a Discourse on the Political Character of Sweden, was published the following year.

Just three years older than Joseph, William George Meredith was born in Marylebone, London, where his father, George Meredith, was an architect. His father and uncle, William Meredith, were friends and patrons of Neo-Platonist Thomas Taylor, the first person to translate the complete works of Aristotle and Plato into English. During their travels to Scandinavia, William was engaged to Sarah Disraeli, the daughter of writer and scholar Isaac D'Israeli. The Merediths and Disraelis had shared a family friendship for years. William was close to Sarah's brother, Benjamin Disraeli, who became the prime minister of Britain in 1868.

Although I am always reluctant to jump ahead in Charlotte's story, wanting the years to move along at their own pace, I cannot help but feel an exception for Joseph and Henry's cousin, William, who is also my second cousin four times removed. The story is that although family friends, William's uncle disapproved of William's betrothal. The Disraeli family were Jewish, and although Isaac D'Israeli left the synagogue and had his children baptized in the Church of England ten years before, William's uncle was adamant. This makes me wonder why his uncle had so much of a voice in the family while William's father, George, was still living. Was his father's health failing? Did his wealthy and generous uncle pay for his schooling and travels? William's uncle proposed that if William spent a year abroad, he would reconsider their union. In 1830, William accompanied Sarah's brother, Benjamin Disraeli, on a year-long journey through Spain, Malta, and the Greek Islands. That December, he left Benjamin and travelled on to Asia Minor. The two met up in Egypt the following summer. William had plans of returning home to London in June but tragically fell ill with smallpox. He died in Cairo the following month, on July 19, 1831, at age twenty-eight. His uncle had passed away several days earlier, and, unknown to William, he had finally consented to their marriage.

|

| William George Meredith's death notice, 21 October 1831, Morning Post, London |

|

| Sarah Disraeli, sweetheart of William George Meredith |

By just the little that I can view online of William's journals, or rather, his commonplace books, I have no doubt William Meredith would have been a significant historian. I also have no doubt that William and Sarah loved each other greatly. William's fiancé Sarah Disraeli never married. In his mother's will that was written in 1856, thirty-five years after her son's death, Esther Gray Meredith, nee Saunders, refers to "beloved Sarah Disraeli" and leaves to her "two thousand pounds three per cent reduced annuities" – a hefty sum today. Sarah Disraeli died in December 1859, and within days of passing away at the age of fifty-four, she bequeaths to William's niece Ellen Higgins a diamond ring given to her by his mother that had belonged to his grandmother Mary Esther Saunders, nee Burbidge. The woman of the family retained a closeness with Sarah that never seemed to fade. And in Sarah's words, "I bequeath to Ellen Gray Mynors, the wife of Robert Baskerville Rickards Mynors of Evenjobb, the only child of my dear friend Georgiana Esther Higgins, an _ diamond ring once belonging to her great-grandmother which is now engraved with her name and date of her death. I leave it to her as I promised her grandmother and with the hope that I may survive after death in her memory in connection with those dear friends I have loved so tenderly in life."

|

| 1856 Will of William Meredith's mother, Esther Gray Saunders, remembering Sarah Disraeli, her son's fiancee. |

It is unknown whether Henry's mother was aware of the matter, but ten years earlier, Henry's father had a son born out of marriage. The son, Henry Griffiths, married Nancy Mitton in 1838 at Bleddfa parish, located not far from Presteigne. The father's name and occupation listed on the parish marriage entry is Henry Ince, surgeon. For some reason, John Price, the rector, fails to include Henry Ince's occupation in the transcripts submitted to the registrar's office. Without viewing the original record, this causes confusion over which Henry Ince was the father. Given the Reverend Beebee's discrepancies in the church records regarding Charlotte, it is unsurprising. There is a good chance that Reverend John Price was acquainted with the Inces, or at least with their closest associates. Could it be that he attempted to shelter Henry Robert Ince's private life? With this in mind, I cannot help but think Henry's father would not be quick to scorn Henry for marrying Charlotte. Perhaps he even envied him for standing up to any public scoff. Sadly, the mother of Henry Griffiths remains unknown. It's quick to come to mind that she may have been a servant in the Ince household, but from all perspectives, she could have been anyone of any background. Although Henry Griffiths' birthplace is given as Presteigne in census records, I find no baptism entry for him in the area. More of his life unfolds in time, but ten-year-old Henry Griffith, Henry's half-brother, remains silent for now.

|

| Evening by Joseph Murray Ince |

Charlotte was coming to the point in her pregnancy where she seldom travelled from home. She was comforted knowing her mother and sisters were not too far away, and Henry could call on them when her time approached. She was anxious to have a visit from Joseph. He had written to them occasionally and did well in his travels, but she knew if she could gaze upon his paintings, even just one, and touch the buildings and sails upon the water, she would comprehend all that he did see. There had been changes, but then again, things always change, although Charlotte may have wondered why. Henry Pyefinch decided that one of their children should live with John James, the son of David Jenkins James. Charlotte knew of the family; everyone in town did. David Jenkins James was a magistrate. His son John was a young unmarried solicitor who leased a house from Henry Pyefinch. It might seem unusual for a single man, such as John James, to raise another man's child in this era of time, but then I am reminded that Henry's Uncle George Saunders, in obliging a good friend's wishes, did the same. Henry P Pyefinch did so as well, when John Fencott asked him to maintain and educate his two grandchildren, George and Charles, "natural" sons born to his late son, John Fencott and Margaret Miles.

The end of the year began to tally, and in early November, as the days were getting shorter, Henry Pateshall Pyefinch sat at his desk, the curtains pulled to keep out the cold. Leaving in just enough light to finish gathering his thoughts, he began to write his last will and testament.

|

| A view of the nine-mile distance and terrain between Knighton, where Charlotte and Henry are living, and Presteigne, their home town. The blue starbursts highlight the two towns |